The role of social media in activist movements is a regular staple of news media. Just recently, political activism in Ukraine over the issue of whether Ukraine should join the European Union has been discussed across several hashtags on Twitter. As the Ukranian state cracked down on protests in Independence square in Kiev, I have been reflecting on the role of Twitter in recent social and political movements. I recently spoke on the BBC Radio 4’s Thinking Allowed about the role of Twitter in social movements and the BBC World Service’s Have Your Say regarding the cases of Ukraine and Thailand more specifically.

More close to home, the UCU, UNISON, and UNITE are striking over fair pay in higher education. And, though much more localized in comparison to Ukraine and Thailand, Twitter is being used (via #fairpayinhe) to coordinate real-time discussion during the strike action. Des Freedman asked me to blog about Twitter and activism as he is staging a ‘teach-out’ (#goldteachout) today during the strike action and wanted to include some material on social media and movements. This blog post attempts to highlight the complex and nuanced role social media plays in contemporary activism using the case of recent events in Ukraine to provide a context.

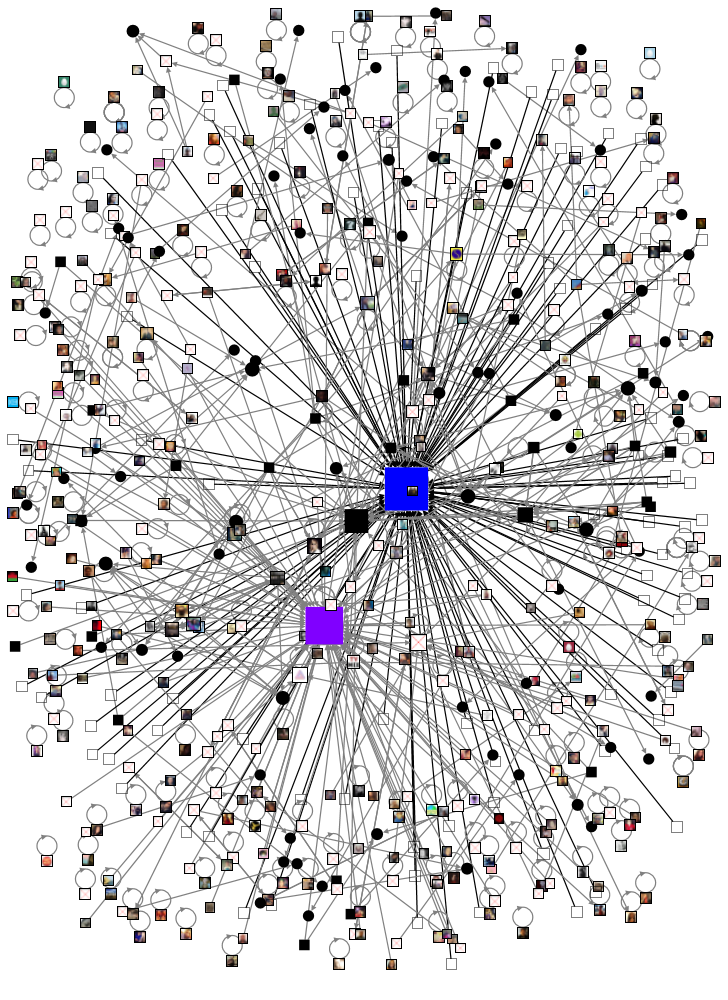

In Ukraine over the weekend, the #Euromaidan hashtag (and, to a lesser extent, #Ukraine) has been used as venue for both citizen journalism and to circulate news regarding the Ukranian protests against President Viktor Yanukovych’s decision to scrap an EU accession deal. Tweets were not restricted to citizen journalists, but included lawmakers as well. For example, Andriy Shevchenko, opposition Ukranian lawmaker, tweeted: “The Maidan has been brutally mopped up,” referring to the government’s violent dispersal of Independence Square in Kiev. On a more micro-level, various social media has been used to circulate firsthand accounts of Independence Square (via YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter).

@ivanbandura TwitPic in Kiev

For example, the Twitter user Ivan Bandura (@ivanbandura), acting as a citizen journalist, tweeted from Kiev: ‘Despite the cold and rain tonight, people still came to protest Ukraine government’s snub to EU #euromaidan pic.twitter.com/G50TX5n0G1’

The violent disbursal by the Berkut (Ukrainian special forces) incensed young Ukranians in Independence Square who turned to Twitter and other ubiquitous social media to report their version of what took place on the ground. As news reports indicate, many of the protesters in Kiev were armed with smart phones. In the case of the Arab Spring, many of the #egypt tweets, for example, were being produced outside of the Middle East. The case of the Ukraine may be the same (with empirical study needed to confirm or discern differences). However, there is a prima facie indication of greater citizen perspectives rather than a glut of celebrity retweets as the tweet below highlights:

“I will get cold or sick, or even die in Kyiv, but I will go [there]! Because otherwise my consciousness would not allow me to live here if everything works out #євромайдан” (from @neksichka via globalvoicesonline)

The Kyiv Post headlined: ‘Role of social media in EuroMaidan movement essential‘, arguing that ‘unlike the Orange revoultion’, Twitter and Facebook were central to EuroMaidan. They report that the frequency of tweets from November 21-28th ranged from 1,500-3,000 (which is not insignificant). Though prima facie, this seems important, it is not the raw frequency that is important as many of these tweets could be retweets of news stories (again, empirical work would be needed to discern this). What did definitively happen is that social media use went up during EuroMaidan. My argument here is not of a Twitter revolution, but that we tweet during activist movements (I found the same during natural disasters such as Hurricane Sandy and the Tōhoku earthquake in Japan).

Any technology that is around/cost-effective/efficient will be used during activist movements. This was true of cassette tapes and photocopies in the 1970’s in Iran and social media today. In other words, the difference is that we now have social technologies that are exponentially more advanced and have far greater reach than older technologies such as faxes or cassette tapes. However, the inherent utility of technology to social activism has not changed in principle. Rather, social media are technologies and just that. Reifying them is dangerous. Rather, social media are used to facilitate activism around issues that have bred sufficient sociopolitical discontent ex-ante (i.e. the discontent is not fomented by the technology per se but rather social technologies are used to inform and rally). In other words, people have been feeling the social issues around them in their everyday lived experience. Social media technologies provide ubiquitous modes of broadcast that can help individuals join global discursive collectives to express those feelings during and after a movement to a wider audience that would not be possible in a localized space. A big difference is also that actors on the ground who are not professional journalists can broadcast their views and experience. Most likely their voice will be blurred into a hashtag – which is not ineffective – and exceptional tweets can be picked up by major news media and circulated to a wide, global audience. Though, it is the exception rather than the rule for tweets to garner a global audience. This highlights a very important point: the efficacy of social media is often dependent on the fact journalists are active on social media and see social media as an integral part of their source mix. Because of this link, social media is important to a movement’s strength on the ‘media battleground’ of winning hearts and minds, an argument made by the Wall Street Journal reporting in Thailand.

As I sit in a cafe writing this, there are three students at a table across from me (one American and one British and one French). I can’t help but overhear as they are talking about the HE strikes. The American says ‘it’s such a British thing to strike’. The British student retorts saying strikes are a very European thing and the French student concurs. It strikes me [pun intended] that it is just this type of discourse which takes place on Twitter during many protests. In other words, perhaps we should be thinking of Twitter as providing a massive public sphere during an activist movement. And like any public space, certain interlocutors have power and influence over others and certain conversations stay micro (like the cafe chat I am eavesdropping on). But unlike the cafe chat, any Twitter conversation can be lifted from obscurity as it is a public medium (and the interlocutors may not even want their tweets to leave the realm of obscurity).

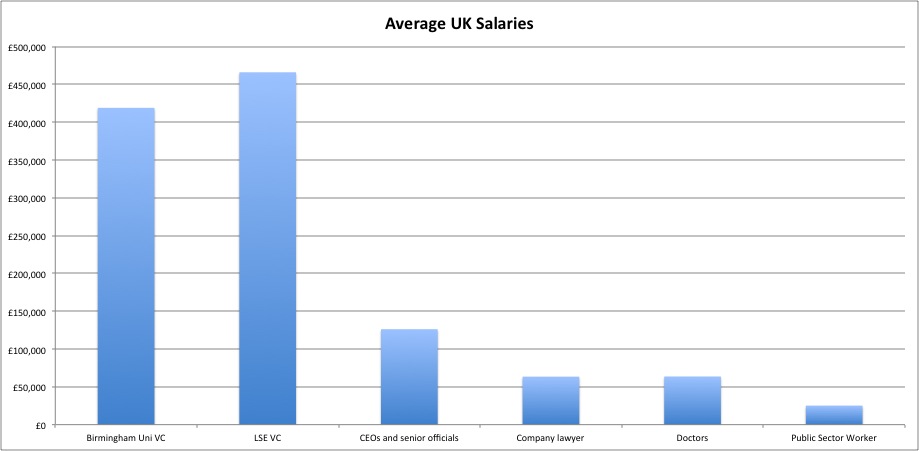

Ultimately, we need to ask whether tweets lead individuals or collectives of protesters, in the case of Thailand for example, to seize government buildings and offices, actions which placed them in direct danger. What I mean is that there must be a compelling motive to bring people to the streets and it is usually not a tweet. In the case of the HE strikes, it is years of unhappiness over low pay that rallied the unions and HE staff to strike (twice). Twitter and other social media can help circulate news and information real time from citizen journalists and journalists alike, but social media are not usually instrumental in breeding the discontent.

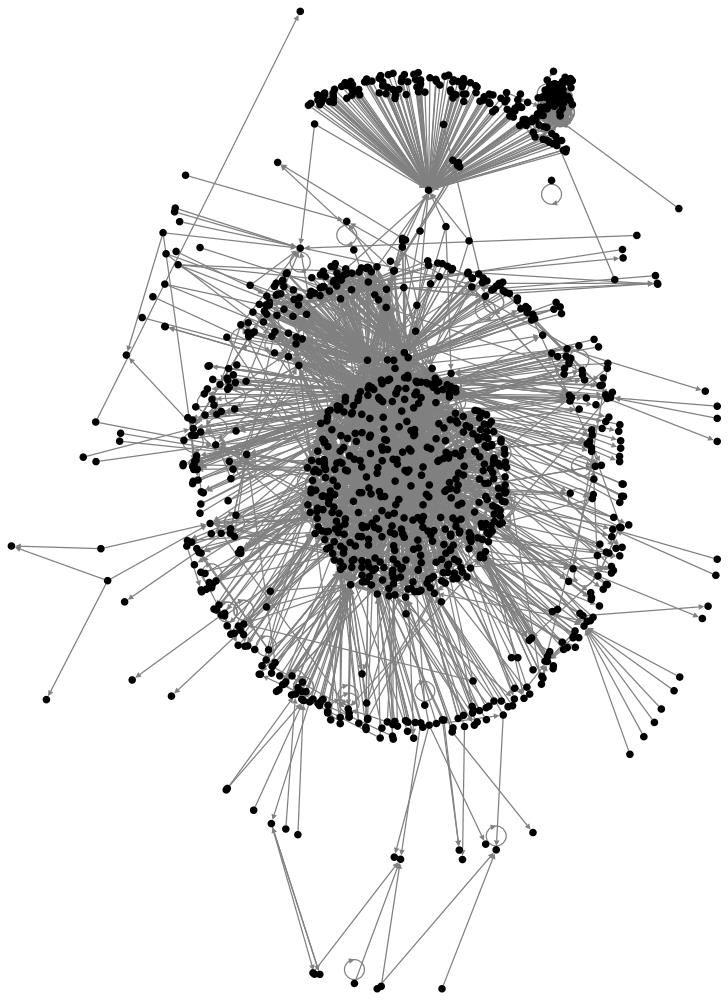

And here is some basic statistics on what is in the tweets:

And here is some basic statistics on what is in the tweets: