Are tweets going to be a thing of the past?

For most reading Twitter’s April 29, 2014 earnings report, the outlook for the popular social media site looks glum. The market read the report one way as evidenced by Twitter’s stock opening down 11.78%. However, slowing user growth should not be equated with Twitter peaking as a social network. Twitter is a complex entity and has gone through various epochs in its short history. Its origins in San Francisco were very much rooted with solving the need for like-minded young tech and media workers to stay updated of social events. It has moved from this narrow remit to what it is today, a household name in social communication. This is not to say that Twitter use has become ubiquitous. User adoption is heavily skewed by age and influenced by region, race, language, and educational level. Indeed, the declining user growth figures are testimony that Twitter has some way to go towards ubiquity. However, though user growth is important, other aspects of the medium are important too. Specifically, Twitter’s recent earnings report highlights that mobile advertising revenue has shot up to 80% of total ad revenue and that mobile monthly active users (MAUs) have gone up by 8% since the last quarter. Twitter is perhaps entering a mobile-oriented period, where it refashions itself in ways to creatively facilitate social networking and social media services on mobile devices. This mobile shift has great potential for Twitter as a more pervasive social network and information network. Specifically, Twitter’s mobile experience has the potential to become attractive to a wider user demographic, enabling the company to add users faster than it has recently.

Will Twitter just be full of fake accounts in 140 days?

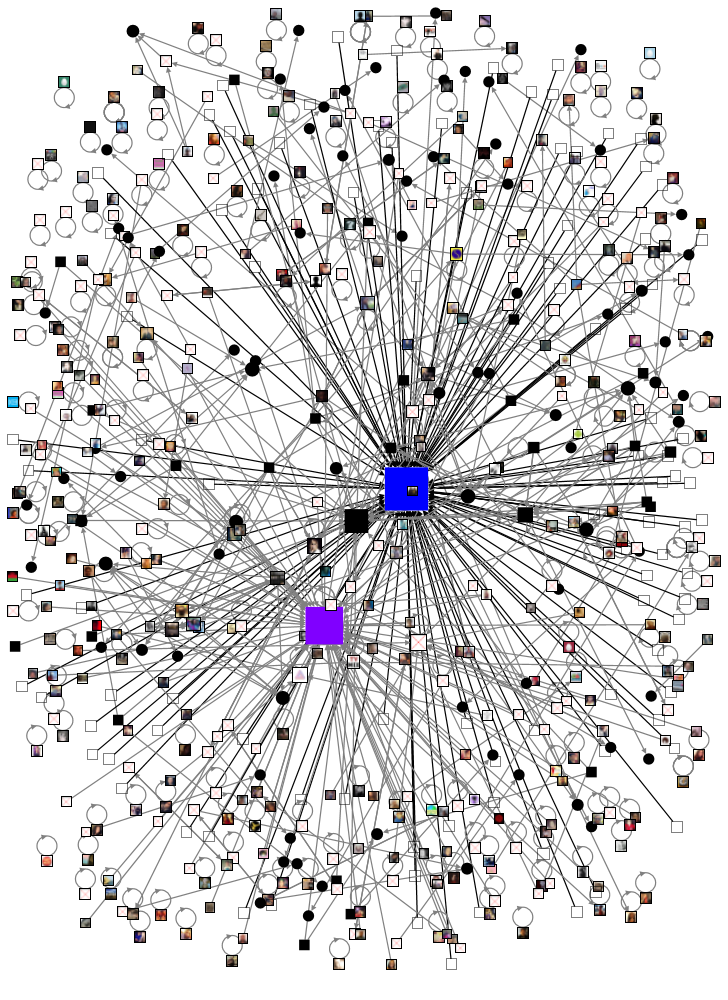

Some argue that Twitter has significant spam, virus, and fake account issues which make the medium hard to navigate and are crippling the user experience. This position sees spam increasing on Twitter. Though malicious uses of Twitter are not insignificant, the medium is not fundamentally experienced as a malicious space for the vast majority of users. Additionally, Twitter as a social space is divided into vast, but intermeshed, subnetworks. These subnetworks often have citizen patrolling functions (not unlike Wikipedia). Of course, like all social media, hoaxes can and do spread on most online social platforms. If we remember back to Hurricane Sandy, Photoshopped images of ominous dark clouds circling the Statue of Liberty went viral across social media as a whole. With Twitter’s 255 million users, patrolling is not always an easy task. However, its power as a social network comes into its own through everyday crowdsourced patrolling on Twitter.

The question of what can Twitter do to limit spam, fake accounts, etc. I think is already being tackled by the social media industry more broadly and Twitter is part of this process. Additionally, the successes of Twitter and its popularity make clear that spam and fake accounts do not dictate most people’s Twitter experience. Indeed, most Twitter users experience significantly higher forms of spam via e-mail and phone and have not abandoned these mediums. Closing down Twitter is more likely to alienate users than spur user growth. Additionally, its power as a global communications medium overshadows spam issues.

One of the unique aspects of Twitter is the ability to send a tweet with anyone in the world and potentially begin a continuing conversation with them. I have had students, for example, tweet to authors of books they are studying and exchanged a couple of highly illuminating tweets with them. Being able to tweet to anyone, of course, can be a double-edged sword in that malicious users can use the medium’s openness in the same ways. But, this is not a major risk and is actually part of the selling point of the very varied uses of Twitter (from social activism to disaster coordination). Indeed some users are active on Twitter for entertainment news and it is meaningful for them to be able to openly tweet at Justin Bieber even though he won’t respond.

People may have more personalized Twitter experiences 140 days from now

Let us not forget that Twitter is many things for many people. Like LinkedIn, Twitter fosters professional networks; like Facebook, it fosters friend networks; like YouTube, Instagram, and Flickr, it fosters media sharing. The medium is perhaps still finding its feet in these areas and a knock-on effect is that its users may be finding new and unique ways to use Twitter that could potentially lead to higher levels of user engagement and growth in the next 140 days to come.

Dick Costolo, Twitter’s CEO has been quite vocal on his thoughts on the subject. Specifically, he has publicly argued that the medium has a larger platform strategy in which mobile is at the heart (I mentioned some of the medium’s growth in this area) and Costolo sees this as game changing. The acquisition of MoPub, a mobile advertising exchange, is testament of Twitter’s commitment to mobile and its moves into more far reaching in-app advertising, which could have major impacts on advertising revenue.

Mass adoption of communications media takes time. However, evidence of the pervasiveness of Twitter to our everyday social lives is really not hard to find. Hashtag culture has been part of the recent Indian elections and billboards from London to Beijing have hashtags. We could see the rise of more localized hashtag-based experiences on the medium.

Twitter’s power is, of course, as a text-based medium. But, my Twitter book makes the sociological argument that Twitter is many things for many people and I think it has great promise in growing its user base amongst those who are tweet-speak phobic by making one type of experience of Twitter highly visual.

Twitter will face challenges in the next 1400 days

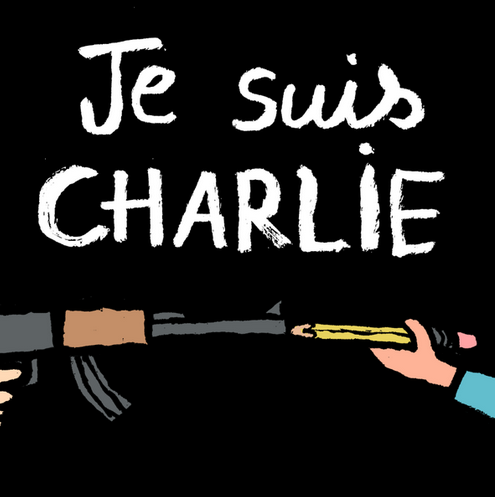

I think Twitter remains unique in many ways in terms of being an open public space. Some scholars have put great hope in Twitter as the bringer of a networked, global public sphere. In a time of increasing government clampdowns on media and moves towards state-censored media, having social media as a potential outlet to voice citizen discontent is fundamentally important to global civil society. Twitter plays an important part in social change movements and reform (both governmental and corporate). It is hardly perfect in this regard, but I remain positive on the outlook for Twitter as an instrument for change. It continues to be used to get the word out on social issues and to organize people (e.g. protest flash mobs). Indeed, the use of Twitter to bring together online and offline activism has been particularly powerful in quite a few cases (though not all!). Additionally, celebrity-led fundraising efforts on Twitter for social causes have been particularly successful due to the prominent role celebrities play on Twitter.

I think in the next 1400 days, Twitter will likely have major user experience changes to try to make the medium more accessible to a wider audience. The lingua franca of Twitter (@, #, tweet, retweet) has created a perceived technical barrier (tweet speak) for many people. I think Twitter is aware of this shortcoming and will likely introduce substantial changes that make the mobile Twitter experience more like texting and email, processes that seem almost second nature to many people around the world.

1400 days is a long time in technology years. However, I think our demands of modern social communication will continue to call for seamless information sharing, public communication, and easy modes of social communication. The latter will definitely remain important and Twitter may continue to uniquely differentiate itself in this area. In other words, a Twitter in 1400 days will still likely be premised on its simplicity of being able to reflect the pulse of the online world. Because of this, Twitter 1400 days from now is likely to be based on open communication. And this openness will likely bring Twitter to more of a center position in data insights and analytics for everyone from the United Nations to small brands. What do people think of X leader or policy? Don’t poll them, tweet them! (Twitter’s acquisition of GNIP is the start of this process.)Though, for this to work, everyday people will need to have a real and meaningful voice on the Twitter of the future. This is not an easy task, but if it is pulled off, it would have real impacts on our social, political and economic lives.

Parts of this article were published as part of a moderated debate in The Wall Street Journal.